Gone and Forgotten: Victims of the Delavan House Fire; December, 1894

From the “Stories of our Dearly Departed” series from Kelly Grimaldi, Historian and Director of Education and Program Development for Albany Diocesan Cemeteries.

In January, Albany Diocesan Cemeteries launched “Stories of our Dearly Departed”, a series featuring stories and photographs of those who are buried within our 19 upstate NY cemeteries.

Our hope is that people will enjoy reading about the lives of our community members just as much as we enjoy learning about them from the families we serve and in the information we find throughout our archives. There are so many fascinating stories buried within these Sacred Grounds!

Gone and Forgotten: Victims of the Delavan House Fire

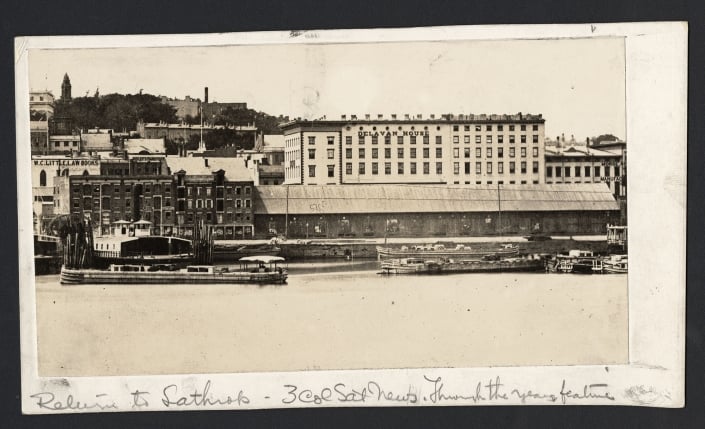

The Delavan House of Albany, New York, was located on Broadway between Steuben and Columbia Streets, and saw more than its fair share of wealthy clientele. Patrons came to Albany from all over the country to enjoy its state-of-the-art accommodations and sumptuous fare. This nationally known destination also served as the country’s political headquarters for four decades. No luxury was spared and the hotel’s gracious hosts and proprietors, Theophilus Roessle and Sons, made certain their “celebrated hotel” lived up to its grand reputation. Under careful management, the Delevan House was transformed from a faltering temperance hotel, to one of “magnificence not inferior to any hotel in this country” according to an article published in the Albany Evening Journal on August 1, 1850. The hotel’s originator and namesake, Edward C. Delevan, was a man of high integrity and intelligence, though his stoic aversion to “strong drink” made him incompatible with the hospitality industry. In a city where the working man had no trouble finding a friendly tavern, and in a city where the fashionable elite imbibed in “strong drink” in a decorous manner, Delavan’s temperance establishment had little appeal. Much to his chagrin, Delavan had to publicly acknowledge his dry hotel had no future. He leased the five-story structure to Roessle, a German immigrant, master gardener and self-made-man. Roessle had a knack for entertaining. He and his sons resuscitated Delavan House in a grand manner with a new décor that included a well-stocked bar. For the next 44 years Delavan House was THE place to be and be seen.

On the evening of December 30, 1894 the hotel was especially lively. Politicians and their wives, newspaper men, industry captains and wealthy land barons were joined together in an event for the candidacy of several men for speaker of the assembly. Ladies and gentlemen of the upper echelons of society mingled among their peers in the grand lobby, elegant tap room and opulent dining room. Men smoked fine cigars and sipped expensive cognac from crystal snifters and discussed the latest political agendas while women gossiped over champagne and sweets. Guests wanted for nothing. Servant girls and young porters discretely stood in the wings waiting to be summoned or dismissed with a careless wave of a manicured hand. Chambermaids remained virtually invisible as though rooms were meticulously prepared by magic. The hotel’s stewards whisked seemingly effortless between linen covered dining room tables laden with plates of fine fare they could never hope to enjoy themselves.

Delavan House glittered at the height of the Victorian Era – a time when unprecedented wealth and unimaginable poverty were accepted as the natural order of things. Neither guest nor servant had any warning their lives were about to be changed forever. At approximately 8:30 PM on that cold winter’s night, the opulent hotel began its rapid descent into a hellish nightmare that continues to fascinate historians today. Delavan House burned to the ground.

The next day every major newspaper throughout the country featured headlines and detailed accounts of the fire. With the usual Victorian flair for drama, the demise of Albany’s famous hotel was told over and over again until fiction clouded a truth that needed no embellishment. Seconds after the first whiff of smoke was detected, cries of fire could be heard in all parts of the hotel. A state of panic gripped guests and sent them into a wild frenzy as they searched frantically for a means to escape. According to a newspaper account published in Fort Wayne News, Fort Wayne, Indiana, “those people on the upper floors could not avail themselves of the exits for the flames were rushing along the corridors forcing them to hang out of windows or dangle on insufficient rope fire escapes.” Horse drawn fire carts arrived within ten minutes but ladders were not high enough to reach the upper two floors. It took only 15 minutes for the entire structure to be wrapped in flames. Most of the guests were rescued or were able to escape unharmed.

Only one fatality made the newspapers, though in total 16 people lost their lives that fateful night. Newspaper articles reported that Mrs. Henry F. Fooks, wife of the agent of the American Cash Register company of Dayton, Ohio “was the only death, she dying at the hospital after having jumped from a fourth story window while her husband clung to the rope fire escape.” Aside from the tragic death of Mrs. Fooks, reporters wrote sympathetically about the terror hotel guests experienced while escaping the flames. And then of course there was the subsequent inconvenience they endured by the loss of their baggage. Some newspaper articles made brief or nonchalant remarks about the loss of hotel staff. Impassionate words used to describe Mrs. Fook’s demise were never printed about the fifteen other souls who were lost that night. Invisible as they were in life, they were even more so in death. It is documented that hotel’s proprietors could not ascertain who was on the payroll that evening. Payroll records burned with the hotel and since many employees were poor immigrants with no family living nearby – nobody was looking for them. The dead were initially described only by their occupations: servants, chambermaids, a pantry girl, two colored cooks and a steward. Many of the 15 dead remained unaccounted for until the last bit of ruins were cleaned off the site in April of 1895. It was then, over four months later, the charred bodies of Irish immigrants Norah Sullivan, 28 and her sister Mary, 21 were found near each together. They were trapped on the fifth floor along with fellow chambermaids Bridget Fitzgibbons and Kate Crowley. The two “colored cooks” who are unnamed until much later were burned as well. Louis Payne, a guest in room 303 when the fire broke out, recalls the steward who gave his life in his effort to alert guests to the fire. “He rushed from room to room pounding on doors until the smoke caused him to fall unconscious to the floor as guests stepped around him in their haste.”

The hotel’s proprietors were forced to conclude that a number of their employees were burned alive that terrible night. Delavan House is gone but will never be a forgotten part of Albany’s history. Gone are the people whose names I have listed below, several resting in St. Agnes Cemetery in Menands. May they rest in peace.

- Mrs. E. H. Hill, housekeeper

- Mary Sullivan, chambermaid

- Mrs. Ray Young, linen woman

- Agnes Wilson, linen woman

- Bridget Fitzgibbons, pantry girl

- Kate Crowley, chambermaid

- Fernando Beletti, cook

- Richard Telesteran, cook

- Metgetta Staurena, chambermaid

- Emilgia Tomigan, chambermaid

- Simon Meyers, employee

- Thomas Cannon, employee

- Annie Daly, chambermaid

- Ellen Dillon, chambermaid

- Norah Sullivan, chambermaid

-Kelly Grimaldi

The Delevan House tragedy is one of our stories available as a “Graveside Chat”. Our Graveside Chats focus on people buried in St. Agnes Cemetery in Menands, NY; capturing their stories and historical themes related to their time. Albany Civic Theater actors bring the deceased to life in this film, dedicated to giving the viewer an accurate account of history. It is poignant, educational and entertaining. The chats are poignant, funny, educational and accurately (as best we could) reconstruct the lives of children, immigrant families, entrepreneurs and ordinary citizens who lived in our area and are buried in St. Agnes Cemetery.

View the The Delavan House Graveside Chat.

The Delavan House fire is also one of many stories featured in our beautiful 160 page coffee table book “These Sacred Grounds: 150 Years of St. Agnes Cemetery” by Historian and Author Kelly Grimaldi, and is now on sale for only $25. Click here for book information.

Do you have a story of an ancestor and/or loved one buried in one of our cemeteries that would be interesting to research and or highlight?

We are looking for stories of those buried within the following 19 cemeteries:

St. Agnes, Menands • Most Holy Redeemer, Niskayuna • St. Anthony’s, Glenville • Our Lady of Angels, Colonie • Immaculate Conception and St. Patrick’s in Watervliet • Our Lady Help of Christians and Calvary in Glenmont • St. Agnes, Cohoes • St. Patrick’s, Coeymans • St. Jean de Baptiste, St. John’s, and St. Mary’s in Troy • Sts. Cyril & Method and Holy Cross in Rotterdam • St. Joseph’s, Waterford • St. John the Baptist and St. Mary’s in Schenectady • St. Mary’s, Coxsackie

If you have a story for us, contact Kelly at 518-350-7679 or [email protected].

Albany Diocesan Cemeteries

Albany Diocesan Cemeteries are operated for the religious and charitable purposes of the Roman Catholic Church through the burial and memorialization of the faithful departed.